Lunar & Solar Calendars vs. Western (Gregorian) Calendars: Solving the Mystery

Before January 1, 1912, when the newly formed Republic of China adopted the Gregorian calendar, Chinese people had been using the traditional lunar calendar for more than 3000 years. Chinese lunar Calendars date back to the Shang Dynasty (late 2nd millennium BC).

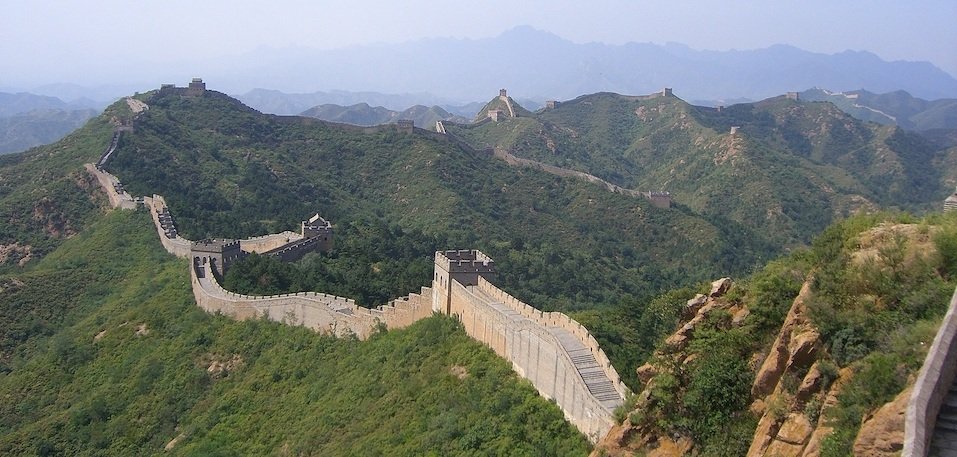

The Great Wall of China

There is much confusion around lunar calendars, solar calendars and Gregorian calendars. Many people don't know that the Western calendar is called Gregorian, named after Pope Gregory XIII, who introduced it in 1582.

Lunar calendars, or "lunisolar" calendars, keep track of months by marking moon cycles. Each lunar new year starts with the second new Moon after Winter Solstice. As with Rosh Hashana, Diwali, and Ramadan, the lunar new year changes every year on the Gregorian (Western) calendar, the civil calendar used in most countries, including the United States.

Calendars track time in a variety of ways across many cultures and languages around the globe. In addition to preserving rich cultural identities and memories, each calendar reveals something about the people who created it.

Traditional Folk Customs at the Spring Festival of China

Several countries celebrate the lunar new year (also known as "Guo Nian" 农历新年 (nónglì xīnnián) or the "Spring Festival" – 春节 (chūnjié).

China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Vietnam, and South Korea all celebrate the lunar new year. It is one of China's most ancient traditional festivals, marked by the beginning of spring and the arrival of a new year. Mongolia, Tibet, and Japan also celebrate certain aspects. Confusingly, these countries also celebrate the solar new year.

Fun Facts: In Mandarin, a common way to wish your family and close friends a happy Chinese new year is "Xīnnián hǎo" (新年好), literally meaning 'new year Goodness' or 'Good new year'.

You can also say "Happy Chinese new year" as "Xīnnián kuàilè" (新年快乐), literally meaning 'new year happiness'. It is a more formal greeting generally used for strangers.

In Cantonese, the common way to say 'Happy lunar new year' is "Gong hei fat choy" (恭喜发财), which means 'Wishing you happiness and prosperity.'

Origins in China

In ancient times, the Chinese gathered around and celebrated the end of the autumn harvest.

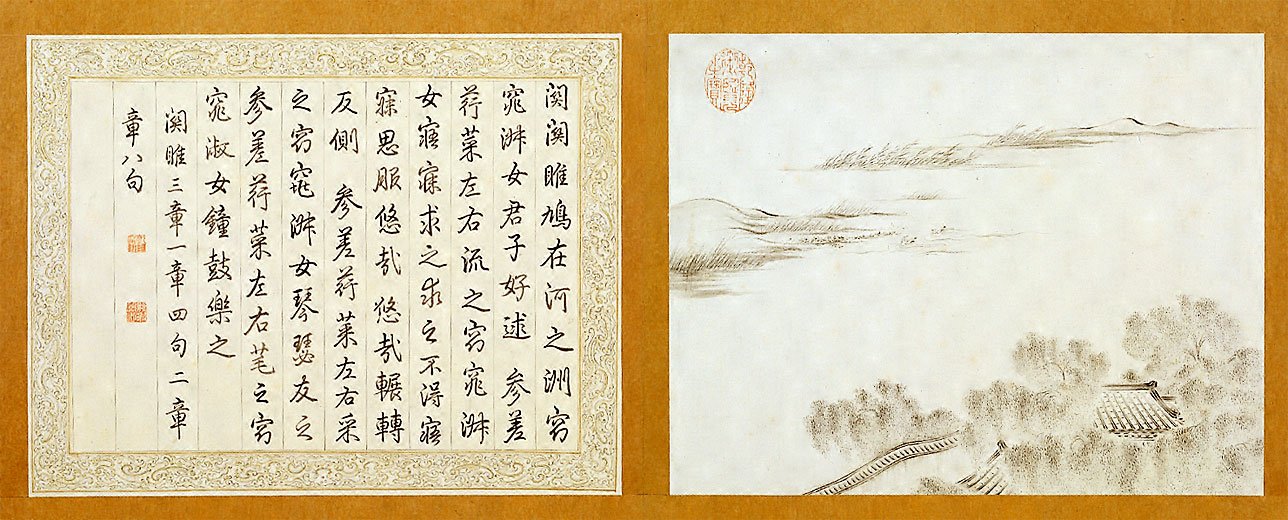

The Classic of Poetry, a poem written by an anonymous farmer during the Western Zhou dynasty (1045 BC – 771 BC), described how people cleaned up millet stack-sites, toasted guests with mijiu (Chinese rice wine made from glutinous rice), cooked lamb, traveled to their master's home, toasted the master, and cheered for long lives together. This festivity happened in the 10th month of an ancient solar calendar, which is believed to be one of the origins of the Chinese new year.

The Classic of Poetry

The first recorded new year celebration occurred in the Warring States period (475 BC – 221 AD). In Lüshi Chunqiu (Master Lü's Spring and Autumn Annals), a radical ritual called "Big Nuo (大儺)" was performed on the last day of the year to expel illness during the Qin period.

Later, after Emperor Qin unified China and the Qin dynasty began, the ritual continued. People would clean up their houses thoroughly to prepare for the new year. They would visit friends' homes and wish each other a happy new year. People also celebrated the new year in the Han dynasty (202 BC - 220 AD).

solar versus lunar

Calendars are always cultural choices, regardless of how scientifically accurate or sophisticated they may be.

The Earth takes 365 days to orbit the sun, which defines the solar year.

The lunar year takes 12 full cycles of the Moon, which is roughly 354 days.

Consequently, a purely lunar calendar - like the Islamic Hijri calendar - is not aligned with the seasons. Islam's holy month of Ramadan may fall in summer one year and winter the next.

Chinese, Hindu, Jewish, and many other calendars are lunisolar to correct seasonal drift. In these calendars, the Moon still defines a month, but an extra month is added periodically to stay on track with the solar year.

A solar calendar is useful for farming, fishing, and foraging societies that need to plan ahead.

The traditional Hijri calendar is marked by the appearance of the crescent moon, which initiates a new month. This emphasizes the importance of paying attention to the cosmos. Gregorian calendars can't be tracked in the skies, so Westerners may need to be made aware of the Moon and other natural phenomena.

Cultural Aspects

Major events on the calendar shape cultural identity. Sukkot, a harvest festival celebrated worldwide, observes the timing of harvest in Israel and preserves a connection in the diaspora (the dispersion or spread of a people from their original homeland).

The holidays also play a significant role in structuring personal narratives and historical narratives. Chinese holidays generally emphasize family unity and honoring ancestors.

Chinese and Mesoamerican calendars also include fortune-telling with instructions for when to build a house, get married, have a funeral, etc. Similar calendars provide structure and comfort to people, even today.

Politics and power usually dictate when a calendar is imposed on a society. Having the ability to declare when a new year will begin or the timing of religious festivals is quite useful for politicians. Historically, staying connected to an alternative calendar can also be a form of resisting the mainstream or maintaining an identity separate from it.

The Gregorian calendar has only been used as a global standard for about a century; it reflects European commerce and colonialism. Computer architecture now incorporates it, but it may still be replaced by another calendar one day.